Watching a young Italian couple struggling to decipher a menu, it occurred to me that being British is a distinct advantage when it comes to travelling through India.

For a start, there’s the language. Not everybody speaks English of course but generally those people who have dealings with tourists – tuk-tuk drivers, shopkeepers, hotel and restaurant staff – speak it well enough to ensure that business can be conducted. A significant number of British tourists visit Goa with the intention of having dental work done cheaply, because it is easy to find English speaking dentists. Educated people may be very fluent so even in banks and post offices that are off the tourist trail, there’s no problem. Sometimes fluency is unexpectedly good – in Varkala we chatted for hours with a Delhi-born Kashmiri shopkeeper, and topics included living costs, legal issues around land sales, and the reprehensible behaviour of some tourists, both Indian and foreign. (As well as being fluent in Hindi, Kashmiri and English he could get by in Malayalam, the language of Kerala where he lived, and could exchange pleasantries in Tibetan with the neighbouring stallholders!). English language newspapers are readily available and if the hotel room has a TV, it’s likely that there will be at least a couple of English language channels. We have the multiplicity of Indian languages to thank for this – more than once we’ve heard restaurant staff speaking English to each other, as the only language they have in common.

The Indian government has tried to instil Hindi as the national lingua franca, but Hindi is completely unrelated to the languages of the south, and the script alien. Southerners resent what they see as an attempt to subjugate their culture – it seems that they prefer to speak the language of a now departed European colonial master than that of what they regard as a present day northern Indian one. Schools in southern states have therefore resisted attempts to make Hindi a compulsory subject, while ambitious parents all over India may chose enrol their children in a school where the entire curriculum is taught in English.

This ability to speak English is of course what has made it possible for so many of the UK’s call centres to be outsourced here, and for Indians to travel to Canada, the US and the UK (in that order of preference) as doctors, dentists, engineers and IT experts. No doubt other European languages are taught in schools and universities, but they are not commonly spoken, so tourists from Germany, France, Italy etc really do need to speak English if they want to travel outside the confines of a tour group – although there are now so many Russian tourists in parts of Goa that menus in Russian are becoming available, and we’ve seen signs advertising Russian classes for hotel staff.

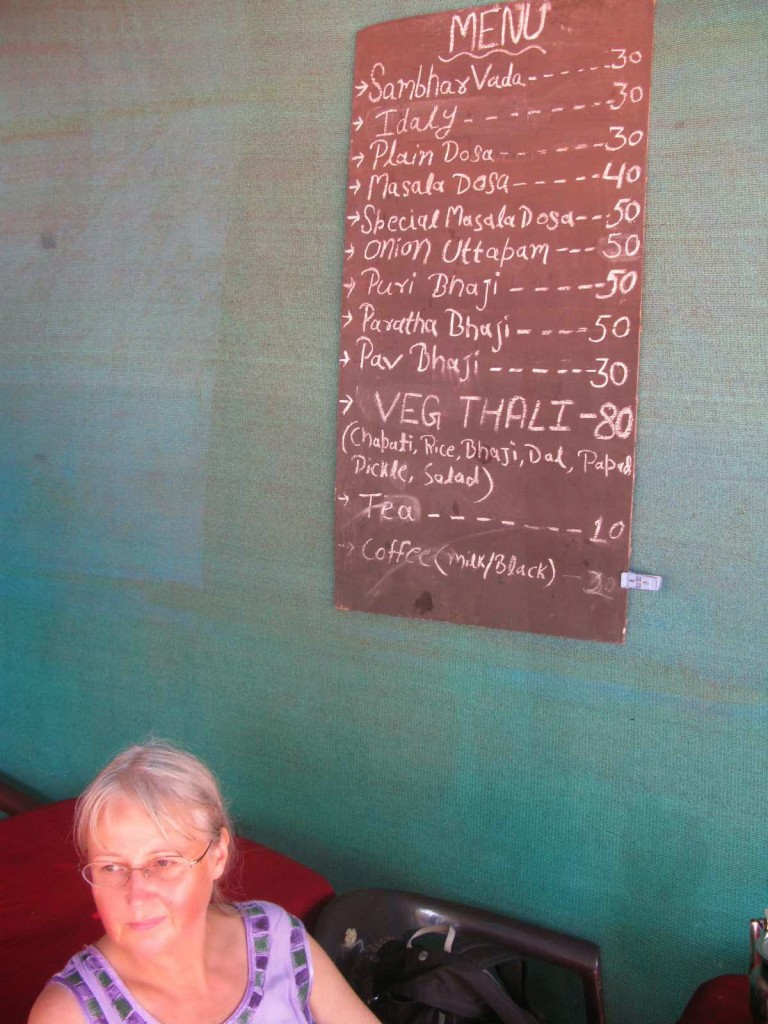

The one glaring gap in the availability of information in English is on menus. Certainly, menus in English are provided in all but the lowliest chai shacks, but the translations are sometimes rather muddled. Making poached eggs out of “pocked eggs”, or peas out of “piece” is not so difficult for a native English speaker, but it must leave others scratching their heads, and “cryed graps” puzzled even us for a while (sultanas!).

However while drinks, breakfasts etc are translated, Indian dishes are generally left as you’d see them on an Indian menu in the UK – aloo gobi, palak paneer, rogan gosht etc – with no further clues to their composition. This is fine for those of us who have had many years experience of ordering Saturday night takeaways, but Indian restaurants are nowhere near as common in many countries outside the UK. We found one in Paris once but it was excruciatingly expensive, and a large town in south west France couldn’t even supply the ingredients to make our own – no fresh coriander in the market and only puy lentils for dhal.

It would be reasonable to assume that many continental European tourists, and Russians, live in towns completely devoid of Indian restaurants – so they may be ordering a totally unfamiliar cuisine without having any idea what the dishes are. No wonder tourist restaurants do a roaring trade in pasta and Chinese food, and Russians fill up on soup (to which they seem particularly partial).

Of course, even the most hardened British curry addict will find unfamiliar dishes on the menu, since the range served in UK restaurants is lamentably limited. But vegetarian dishes are always listed separately from non-veg, so sometimes you just have to take a chance. I know now that fish (and presumably anything else) hariyali means a vibrant green sauce of spinach, mint and coriander, but I’m still not sure what distinguishes a vegetable kohlapuri from a vegetable jaipuri (but they’re both nice).

We’re lucky in Reading to have Cafe Madras (venue for our regular masala dosa fix) – I think I would find living somewhere without access to decent Indian food a real hardship (ironic, since I didn’t even like it for the first 30 years of my life – or at least, I didn’t like what passed for curry in 1970s and 80s Britain, which was nothing like Indian food). I think I may go into DTs shortly after we leave India – Indonesian food is an unknown area for me, other than satay.

The Indonesian language is also new to me, and since English is not so widely spoken there I’m trying to learn enough to get by. In some ways it’s an easy language to learn – no noun genders, no plethora of verb endings to reflect tense or person, not even an equivalent for “to be”. The main thing to get right is word order – the difference between “rumah anda” and “anda rumah” is the difference between “your house” and “you are a house”, so the potential for confusion (and offence!) is significant.

Still, I’ve managed to learn almost 200 words in 6 weeks, which is more than the Hindi that I acquired in 2 years. However, I have barely scratched the surface of the items that we may encounter on a menu, so we may well end up in the same position as many tourists here.