Collecting the car was a simple enough matter. Neither of us had driven for almost 2 years, but Darwin’s quiet, wide streets and simple grid layout was as gentle a reintroduction as it could be. Fitting everything into the car wasn’t quite so easy, with boxes of food and a 20 litre container of water (scrounged from Zen’s café, it had previously held vinegar).

The route from Darwin to Jabiru is pretty simple – head down the Stuart Highway, the main road out of town, turn left at Humpty Doo, 36km out of town, and just keep going along the Arnhem Highway for another 220km. Pretty hard to get lost!

We stopped to eat our sandwiches at Window on the Wetlands, a visitor centre with displays illustrating the local ecology 30km after Humpty Doo. Sitting at a picnic table at the edge of the car park, we had a view over the plains below – at this time of year the name could not have been less apt. The spindly trees still had green leaves, but the ground below was covered in parched grass. Several columns of smoke rose from distant wildfires. Apart from birds the only wildlife visible was a small group of buffalo – farmed or feral, we couldn’t tell.

It was a long drive to our next stop at the Mamukala wetlands. Even with the A/C on full blast it was hot in the car, and the endless miles of dry forest and empty road, together with the lack of radio stations, made us both feel sleepy. We resolved to dig out a USB stick so that we had music for the rest of the trip.

It was only a short walk from the car park to the viewing platform at Mamukala, but we had our first glimpse of a live macropod as a wallaby bounced away through the trees. Up to that point we had only seen dead ones, of various sizes, by the side of the road. The Mamukala billabong was a vast, pink lily covered area hosting thousands of water birds – the black and white Magpie Geese for which it’s most known, but also clusters of Whistling Ducks on the muddy shore, and an assortment of waders.

From Mamukala to Jabiru was only 20 minutes, and the Kakadu Lodge was easily found. This was to be the most expensive and yet worst equipped accommodation of our trip – two rows of former miners’ bunkhouses had been converted to double rooms equipped with A/C, TV and fridge-freezer, but with no bathrooms. But it was OK – our room was only a few steps from the toilet and shower block, and there was a decently equipped shared kitchen in the row beyond.

The site was circular with an awning-shaded pool, bar and bistro at the centre and camping and caravan pitched arranged in concentric circles around it. At the edges were cabins and standing camps used by tour companies. There isn’t much accommodation in Kakadu, so it’s excruciatingly expensive – a cabin with an ensuite bathroom would have cost over A$200 a night, and a room at the crocodile-shaped Mercure hotel up the road even more. Anticipating high prices at the bistro and with no more economical eating places available, we’d brought food for the first two days – the cooking facilities were better than we expected, so we paid a visit to Jabiru’s sole supermarket and bought ingredients for the rest.

Nourlangie was only half an hour from Jabiru – an escarpment of sandstone and conglomerate with aboriginal paintings in several spots. A large party of teenagers had arrived at the car park just before us, but we managed to stay ahead of them most of the time. It was fiercely hot, but so dry that I only realised how much I was sweating when I licked my lips and tasted salt. The water in my bottle was unpleasantly warm, but I drank it anyway. The flies were a pest, trying to land on our faces, and we had to flick our scarves constantly to keep them away.

The nearby Bowali visitors centre was another natural history display, but there were also exhibits relating to aboriginal culture, and hints at the difficulty of maintaining their land. There is a uranium mine at Jabiru, and they are under constant pressure to allow exploitation of gold and other mineral deposits that are known to be in the area.

Ubirr, about 40 minutes north of Jabiru, is the best known rock art site in the area. We’d set out early to beat the heat, and also beat most of the crowds. We didn’t really have any of the sites to ourselves, but there were only a few others. The rocky outcrops here were smaller than Nourlangie’s escarpment, but the paintings more numerous and better executed.

A little way back along the road, a turning opposite the Border Store led to a car park by the river. The Border Store is actually just a cafe really, although bizarrely it specialised in Thai food, with perhaps the most expensive pad Thai in the world.

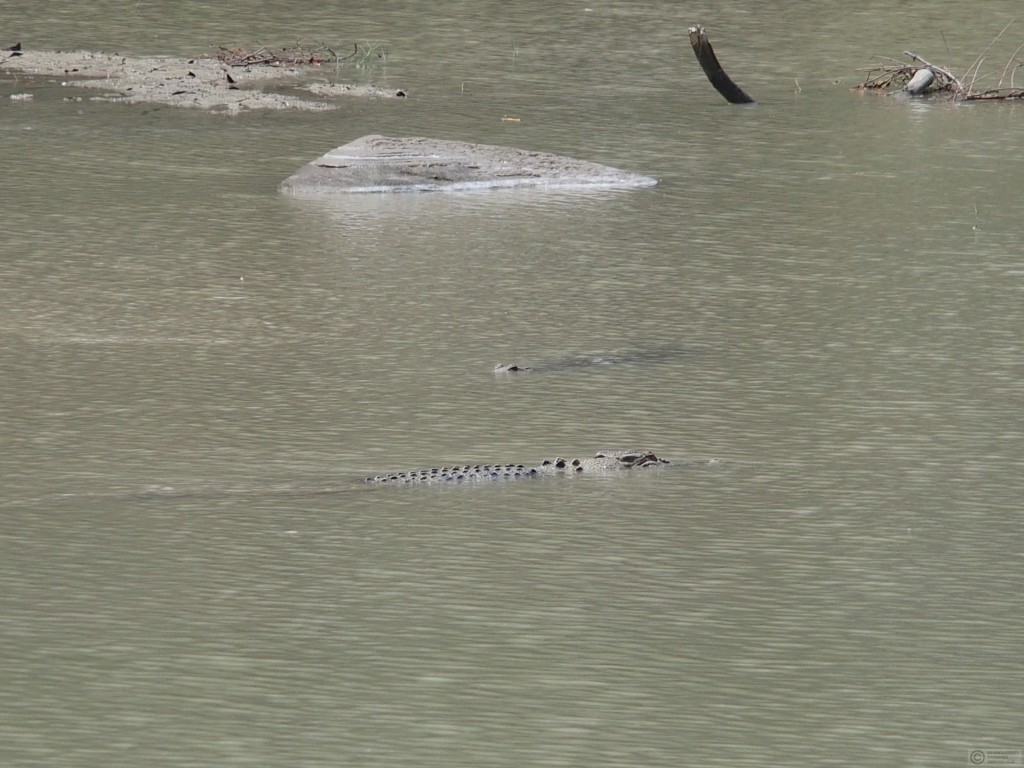

From the car park, a boat ramp led down into the water of the East Alligator River. Signs warned against the cleaning of fish on the ramp. It was too muddy to see anything below the surface, but it wasn’t long before a pair of eyes popped up. They stared at us for a short while before moving slowly upstream towards the causeway of Cahill’s Crossing, where the road crosses into the vast area of Aborigine held Arnhemland. Only the crocodile’s back, eyes and nose tip were visible so it was difficult to estimate size, but it was certainly large enough to ruin someone’s day. But a couple of guys were rod fishing from the causeway – had they never watched Crocodile Dundee?

The Manngarre Walk, a narrow, winding path through dry forest, also left from the car park. Its most notable sight was hundreds of fruit bats roosting in the trees. It would have been hard to miss them – they have a distinctive smell (not unpleasant), and can’t resist squabbling and squeaking.

After so much driving, we decided to have a day off and just walk around Jabiru. Flocks of noisy white cockatoos fussed and flapped in the trees, descending to the ground wherever there was a chance of a drink from a caravan site sprinkler – a puddle left by a hosepipe attracted a large gathering.

Jabiru Lake is a decent size – large enough that we didn’t want to walk all the way around it in the heat. The usual assortment of water birds were busy doing their thing there; a single Jabiru stork, whistling ducks, geese, and a Jacana carefully stepping across the lily pads, its long, slender toes spreading its weight.

Jabiru exists because of the nearby uranium mine, and the miners live in neat modern bungalows arranged in a cluster of cul-de-sacs. Very, very few of them are indigenous Australians – they live in a separate area on the other side of the lake, their homes hidden from tourist eyes. Both communities use Jabiru’s limited facilities – a supermarket large enough to supply all needs provided you don’t want anything too exotic, a bakery, cafe, jobcentre, bank, school, clinic, garage and police station. But the mine only has consent to operate until 2021, and the aboriginal council seems unlikely to renew that consent (which they didn’t freely give in the first place). Tourists help sustain the supermarket and petrol station in the dry season, but if all the miners and their families leave it’s hard to see how all the services in Jabiru will survive with only half its current population.

What is notably unavailable in Jabiru centre is retail alcohol – if you want a drink you have to go to the hotel, the sports & social club, or the bistro at Kakadu Lodge. To buy at a supermarket you have to drive to Darwin! Unfortunately alcohol abuse is a very significant issue among aborigines, so many places in the Northern Territory have restrictions on sales.

At dusk I went for a walk around the camp site. It was interesting to compare the equipment that people travelled with. At one end of the scale were four bivvy bags laid on the grass next to a dusty Land Rover type of vehicle. Obviously they were banking on no rain. Little one-person dome tents stood alone in the sun waiting their owners’ return – they must have been hellish hot inside. At the top end were huge caravans, RVS and trailer tents. Behind one trailer a family sat around a table watching a large flat screen TV. Another trailer set-up boasted a separate awning with what looked like a fully fitted kitchen, complete with a standard fan. Six large potted plants flanked the steps of a caravan. On one pitch, a 4WD, a trailer, a caravan and a motorbike were covered by huge awnings that must have taken hours to erect. At what point does camping become kind of pointless? Perhaps it’s just about the economics, but all that equipment must cost a fortune!